Monday, June 05, 2006

Sunday, June 04, 2006

The Computer As A Musical Medium

Download

Infanticide.mp3 [3.6meg]

Introduction

The aim for this assignment was to create a soundscape depicting the inner mind of a woman in the midst of a mental breakdown.

Credits

Brisbane poet, Rosanna Licari, contributed a reading of her poem entitled Verge for this recording.

Equipment Used

Vocals and live audio recorded with a Roland VS1680 Digital Workstation and a Sennheiser MD416 microphone.

The background sound wash was created with sounds from a Roland JV1080, Roland U220, Roland A90ex, Roland SC88Pro and Yamaha DX7s.

Vocal and other live audio samples were treated with effects such as pitch shift in Sonic Foundry's Sound Forge.

Cakewalk Sonar 3.1 PE was used to assemble all the elements, apply spatial effects and EQ, mix down the final result and burn it to CD.

Methods

Inspiration for Infanticide came in part from Bret Easton Ellis's novel American Psycho and his use of a writing technique called "the unreliable narrative". It is a technique whereby the reader is led to believe something happened but ultimately is left unsure as to whether anything really did happen, or whether the main character imagined it all. Other inspiration came from readings of Lewis Carroll's fantasy works and an idea that the computer as a medium has the ability to channel abstract thoughts into reality. This is all discussed more fully in the accompanying essay: How The Computer Can Be Used As A Medium.

Rosanna's original poem was a continuous and coherent narrative of a woman remembering her childhood. After recording her reading, I transferred it into Sound Forge, extracted several key phrases from it and discarded the remainder. Phrases were chosen on the basis of the aesthetic quality of the timbre and inflections in Rosanna's voice. From the outset, I conceived the inner mind of this woman as being filled with voices - her own voice, but disembodied from its source.

The phrases were divided into three groups that in turn would form three layers of the soundscape. The phrases for the foreground were essentially untreated, except for some reverb to give them a light, ethereal quality. The two other layers were both heavily treated, particularly with EQ and a spatial 3-D reverb effect that was automated to make them swirl around the soundscape. They were also repeated in a way that created a vague sense of rhythm each time they recurred. Expansion and contraction of these phrases also enhanced the irregular rhythmic effect.

Layering multiple sources of similar sounding tones from various sound modules created the background drone. These were subtly mixed so that different frequency ranges of the tones faded in and out. A number of audio samples were also combined, such as the "breath" (the sound of compressed air from an aerosol can) that rises and falls in the background. A "heartbeat" pulse was also recorded for the background but later discarded for being too cliché. The music box recording of Greensleeves is positioned with reverb so that it sounds like it's outside of the woman's head as she finally loses whatever tenuous grip she had on reality to begin with.

Results

The finished soundscape is very faithful to my original conception of it. I am particularly pleased with the hypnotic effect of Rosanna's voice and its various treatments. I also like the way there seems to be a narrative happening and that it almost makes sense. However, it's an unreliable narrative and ultimately the listener is left unsure of whether this woman has really killed her own infant or if any child even existed to begin with. The Greensleeves reference works on several psychological levels. At one level, it is the sound most Australians would associate with ice cream vendors and thus acts as a fond memory she might have of her own childhood. At another more abstract level, it's a composition attributed to King Henry VIII and thus creates a kind of connection to women being executed because of their inability to have children.

Conclusions

This soundscape creation is only possible because of the technology used to create it. Aside from the channeling of an imaginary audio landscape into reality, the methods employed in its composition were more like painting a picture than composing music in any traditional sense. For me, this was a very relaxing and satisfying artistic experience.

How A Computer Can Be Used As A Musical Medium

Abstract

This paper examines the concept of computers as a musical medium. The word medium has many definitions. Among them is "a person thought to have the power to communicate with...agents of another world or dimension."[1] Sceptics argue that such people are deluded or out of touch with reality but if disbelief is suspended and the computer considered as something that can channel fantasy into reality, then a case could be argued that a computer can actually act as this kind of medium.

Introduction

Christopher Longuet-Higgins in Musical Structure and Cognition (ed. Howell, Cross and West: xi)[2] describes music as "perhaps the most mysterious of all the arts, being at the same time so remote from reality and so faithful to experience." To talk about reality at all is to talk about our perception of it. Perception is shaped by experiences, both real and imagined and these combine to create memories. Memories enable us to compare and contrast experiences, our perceptions of them and thus define our reality. One of the prime characteristics of the computer as a medium is its ability to blur this reality and by extension, alter our state of consciousness.

Virtual Realities

Lewis Carroll's stories of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through The Looking Glass both provide good illustrations of blurred realities created in the literary medium. They conjure worlds in which big is small, up is down, and so on. For a child, these stories challenge their perception of the world they know. It is the same challenge faced by the character of Neo in the Matrix films and the Virtual Reality world in which the films are set. It is a computer world where none of the usual laws of physics apply, just as Wonderland was for Alice. At a deeper, more philosophical level, both explore concepts of morality, choice and a search for meaning.

Carroll's Jabberwocky poem could also be a metaphor for today's news media - a medium that presents to us a reality but which is filled with Orwellian double-speak and jibberish. Alice's statement after reading Jabberwocky sums it up very eloquently:

"...it's rather hard to understand!" (You see she didn't like to confess, ever to herself, that she couldn't make it out at all.) "Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideas - only I don't know exactly what they are! However, somebody killed something: that's clear, at any rate..."[3]

A Playground For Musical Fantasy

The references to Carroll have been used to highlight an important facet of the computer as a musical medium and in particular, the methods by which it can represent things that otherwise could only be imagined. When Alice first begins to read the Jabberwocky poem, it makes absolutely no sense to her at all because the typeface is all reversed. It dawns on her that the poem can only have meaning if its words are reflected in a mirror. If one was to make an audio recording of a reading of Jabberwocky using computer software, the medium is such that it can easily be played in reverse thus allowing the listener to hear the poem actually spoken as Carroll might have imagined. In a sense, it could be said that Carroll's creative spirit is being channelled directly through the medium.

Similarly, the computer can act as a musical medium to channel any sound a person might be able to imagine from their thoughts and into a world where everybody can hear them. If there is any limitation to this, it's unlikely the computer medium is at fault. Rather, the only possible limitation will be that of the human operator's imagination and their ability to use the sonic manipulation capabilities of various music software programs.

Taboos, Invention and Creativity

In music, just as in life, there are many taboos. By definition, these are strong social prohibitions relating to human activity or social custom declared as sacred and forbidden; breaking of the taboo is usually considered objectionable or abhorrent by society.[4] What is particularly interesting, however, is that taboos are social conventions that exist in reality but not necessarily in the human mind. There seems to be a consensus among those who have studied creativity (Csikszentmihalyi et. al.) that creative individuals are aware of traditions but aren't afraid to challenge and break from them.[5]

Throughout music history, various musical taboos have been broken. Perhaps the most significant break was when western music was liberated from its role as purely religious and devotional to become a secular entertainment. The tritone interval, once called diabolus in musica or the Devil's interval in the early music era through to the Baroque, is now in common use across a range of musical styles.

In the past 100 years, many things once considered purely as noise and thus a taboo in music are now regarded as new and exciting timbres in the creation of new sounds. Technological advances have made this possible in music though there are many parallels in other fields of artistic expression as well. The invention of electricity not only paved the way for the capturing, storing, manipulation and dissemination of sounds. It made possible dozens of new forms of visual arts, from motion pictures to laser light sculptures and for the integration of these with sound and music. More than this, these combinations themselves - borne in the imaginations of creative people - can be channelled through the computer medium to form virtual worlds that are greater than the sum of their parts.

Conclusion

Sceptics might argue, just as they do about psychics, that the disembodiment of one sound from its traditional context to create another and the channelling of it into something labelled as "music" is the work of charlatans. It is certainly the case that the computer as a musical medium challenges traditional analysis and meaning of music but then, the very nature of music has eluded scholars for well over three thousand years.[6]. As a phenomenon, music is ubiquitous and universal and yet its existence remains unexplained by any apparent practical purpose. Perhaps the best explanation might be simply that our entire perception of reality is flawed by the nihilism so prevalent in today's culture. If the computer medium really is the conduit between some other world or dimension and this one, just as the rabbit hole was Alice's portal into Wonderland, then the future as I see it looks as bright and meaningful as any I can imagine.

"Reality: a nice place to visit, but I wouldn't want to live there." (Anonymous)

References

1 Dictionary.com (2006), Medium, http://dictionary.reference.com/search?q=medium, Accessed 20 May, 2006.

2 Howell, P., Cross, I., and West, R. (Eds.), (1985) Musical Structure and Cognition, London: Academic Press.

3 Literature.org, (2005), Lewis Carroll: Through The Looking Glass, http://www.literature.org/authors/carroll-lewis/through-the-looking-glass/chapter-01.html, Accessed 20 May, 2006.

4 Wikipedia, (2006), Taboo, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taboo, Accessed 20 May, 2006.

5 Csikszentmihalyi, M., (1996) Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention, New York: Harper Collins.

6 Serafine, M. L., (1988) Music As Cognition: The Development of Thought in Sound, New York: Columbia University Press.

Infanticide.mp3 [3.6meg]

Introduction

The aim for this assignment was to create a soundscape depicting the inner mind of a woman in the midst of a mental breakdown.

Credits

Brisbane poet, Rosanna Licari, contributed a reading of her poem entitled Verge for this recording.

Equipment Used

Vocals and live audio recorded with a Roland VS1680 Digital Workstation and a Sennheiser MD416 microphone.

The background sound wash was created with sounds from a Roland JV1080, Roland U220, Roland A90ex, Roland SC88Pro and Yamaha DX7s.

Vocal and other live audio samples were treated with effects such as pitch shift in Sonic Foundry's Sound Forge.

Cakewalk Sonar 3.1 PE was used to assemble all the elements, apply spatial effects and EQ, mix down the final result and burn it to CD.

Methods

Inspiration for Infanticide came in part from Bret Easton Ellis's novel American Psycho and his use of a writing technique called "the unreliable narrative". It is a technique whereby the reader is led to believe something happened but ultimately is left unsure as to whether anything really did happen, or whether the main character imagined it all. Other inspiration came from readings of Lewis Carroll's fantasy works and an idea that the computer as a medium has the ability to channel abstract thoughts into reality. This is all discussed more fully in the accompanying essay: How The Computer Can Be Used As A Medium.

Rosanna's original poem was a continuous and coherent narrative of a woman remembering her childhood. After recording her reading, I transferred it into Sound Forge, extracted several key phrases from it and discarded the remainder. Phrases were chosen on the basis of the aesthetic quality of the timbre and inflections in Rosanna's voice. From the outset, I conceived the inner mind of this woman as being filled with voices - her own voice, but disembodied from its source.

The phrases were divided into three groups that in turn would form three layers of the soundscape. The phrases for the foreground were essentially untreated, except for some reverb to give them a light, ethereal quality. The two other layers were both heavily treated, particularly with EQ and a spatial 3-D reverb effect that was automated to make them swirl around the soundscape. They were also repeated in a way that created a vague sense of rhythm each time they recurred. Expansion and contraction of these phrases also enhanced the irregular rhythmic effect.

Layering multiple sources of similar sounding tones from various sound modules created the background drone. These were subtly mixed so that different frequency ranges of the tones faded in and out. A number of audio samples were also combined, such as the "breath" (the sound of compressed air from an aerosol can) that rises and falls in the background. A "heartbeat" pulse was also recorded for the background but later discarded for being too cliché. The music box recording of Greensleeves is positioned with reverb so that it sounds like it's outside of the woman's head as she finally loses whatever tenuous grip she had on reality to begin with.

Results

The finished soundscape is very faithful to my original conception of it. I am particularly pleased with the hypnotic effect of Rosanna's voice and its various treatments. I also like the way there seems to be a narrative happening and that it almost makes sense. However, it's an unreliable narrative and ultimately the listener is left unsure of whether this woman has really killed her own infant or if any child even existed to begin with. The Greensleeves reference works on several psychological levels. At one level, it is the sound most Australians would associate with ice cream vendors and thus acts as a fond memory she might have of her own childhood. At another more abstract level, it's a composition attributed to King Henry VIII and thus creates a kind of connection to women being executed because of their inability to have children.

Conclusions

This soundscape creation is only possible because of the technology used to create it. Aside from the channeling of an imaginary audio landscape into reality, the methods employed in its composition were more like painting a picture than composing music in any traditional sense. For me, this was a very relaxing and satisfying artistic experience.

How A Computer Can Be Used As A Musical Medium

Abstract

This paper examines the concept of computers as a musical medium. The word medium has many definitions. Among them is "a person thought to have the power to communicate with...agents of another world or dimension."[1] Sceptics argue that such people are deluded or out of touch with reality but if disbelief is suspended and the computer considered as something that can channel fantasy into reality, then a case could be argued that a computer can actually act as this kind of medium.

Introduction

Christopher Longuet-Higgins in Musical Structure and Cognition (ed. Howell, Cross and West: xi)[2] describes music as "perhaps the most mysterious of all the arts, being at the same time so remote from reality and so faithful to experience." To talk about reality at all is to talk about our perception of it. Perception is shaped by experiences, both real and imagined and these combine to create memories. Memories enable us to compare and contrast experiences, our perceptions of them and thus define our reality. One of the prime characteristics of the computer as a medium is its ability to blur this reality and by extension, alter our state of consciousness.

Virtual Realities

Lewis Carroll's stories of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through The Looking Glass both provide good illustrations of blurred realities created in the literary medium. They conjure worlds in which big is small, up is down, and so on. For a child, these stories challenge their perception of the world they know. It is the same challenge faced by the character of Neo in the Matrix films and the Virtual Reality world in which the films are set. It is a computer world where none of the usual laws of physics apply, just as Wonderland was for Alice. At a deeper, more philosophical level, both explore concepts of morality, choice and a search for meaning.

Carroll's Jabberwocky poem could also be a metaphor for today's news media - a medium that presents to us a reality but which is filled with Orwellian double-speak and jibberish. Alice's statement after reading Jabberwocky sums it up very eloquently:

"...it's rather hard to understand!" (You see she didn't like to confess, ever to herself, that she couldn't make it out at all.) "Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideas - only I don't know exactly what they are! However, somebody killed something: that's clear, at any rate..."[3]

A Playground For Musical Fantasy

The references to Carroll have been used to highlight an important facet of the computer as a musical medium and in particular, the methods by which it can represent things that otherwise could only be imagined. When Alice first begins to read the Jabberwocky poem, it makes absolutely no sense to her at all because the typeface is all reversed. It dawns on her that the poem can only have meaning if its words are reflected in a mirror. If one was to make an audio recording of a reading of Jabberwocky using computer software, the medium is such that it can easily be played in reverse thus allowing the listener to hear the poem actually spoken as Carroll might have imagined. In a sense, it could be said that Carroll's creative spirit is being channelled directly through the medium.

Similarly, the computer can act as a musical medium to channel any sound a person might be able to imagine from their thoughts and into a world where everybody can hear them. If there is any limitation to this, it's unlikely the computer medium is at fault. Rather, the only possible limitation will be that of the human operator's imagination and their ability to use the sonic manipulation capabilities of various music software programs.

Taboos, Invention and Creativity

In music, just as in life, there are many taboos. By definition, these are strong social prohibitions relating to human activity or social custom declared as sacred and forbidden; breaking of the taboo is usually considered objectionable or abhorrent by society.[4] What is particularly interesting, however, is that taboos are social conventions that exist in reality but not necessarily in the human mind. There seems to be a consensus among those who have studied creativity (Csikszentmihalyi et. al.) that creative individuals are aware of traditions but aren't afraid to challenge and break from them.[5]

Throughout music history, various musical taboos have been broken. Perhaps the most significant break was when western music was liberated from its role as purely religious and devotional to become a secular entertainment. The tritone interval, once called diabolus in musica or the Devil's interval in the early music era through to the Baroque, is now in common use across a range of musical styles.

In the past 100 years, many things once considered purely as noise and thus a taboo in music are now regarded as new and exciting timbres in the creation of new sounds. Technological advances have made this possible in music though there are many parallels in other fields of artistic expression as well. The invention of electricity not only paved the way for the capturing, storing, manipulation and dissemination of sounds. It made possible dozens of new forms of visual arts, from motion pictures to laser light sculptures and for the integration of these with sound and music. More than this, these combinations themselves - borne in the imaginations of creative people - can be channelled through the computer medium to form virtual worlds that are greater than the sum of their parts.

Conclusion

Sceptics might argue, just as they do about psychics, that the disembodiment of one sound from its traditional context to create another and the channelling of it into something labelled as "music" is the work of charlatans. It is certainly the case that the computer as a musical medium challenges traditional analysis and meaning of music but then, the very nature of music has eluded scholars for well over three thousand years.[6]. As a phenomenon, music is ubiquitous and universal and yet its existence remains unexplained by any apparent practical purpose. Perhaps the best explanation might be simply that our entire perception of reality is flawed by the nihilism so prevalent in today's culture. If the computer medium really is the conduit between some other world or dimension and this one, just as the rabbit hole was Alice's portal into Wonderland, then the future as I see it looks as bright and meaningful as any I can imagine.

"Reality: a nice place to visit, but I wouldn't want to live there." (Anonymous)

References

1 Dictionary.com (2006), Medium, http://dictionary.reference.com/search?q=medium, Accessed 20 May, 2006.

2 Howell, P., Cross, I., and West, R. (Eds.), (1985) Musical Structure and Cognition, London: Academic Press.

3 Literature.org, (2005), Lewis Carroll: Through The Looking Glass, http://www.literature.org/authors/carroll-lewis/through-the-looking-glass/chapter-01.html, Accessed 20 May, 2006.

4 Wikipedia, (2006), Taboo, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taboo, Accessed 20 May, 2006.

5 Csikszentmihalyi, M., (1996) Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention, New York: Harper Collins.

6 Serafine, M. L., (1988) Music As Cognition: The Development of Thought in Sound, New York: Columbia University Press.

Sunday, April 23, 2006

Happenstance

Happenstance: Analysis

DOWNLOADS:

Happenstance - Full Mix.mp3

Happenstance - Piano Trio Mix.mp3

Happenstance - Score.pdf

The Concept

Happenstance, as the title suggests, was composed from a few simple musical ingredients to yield a rhythmically complex and surprising score. A single scale source, namely an 8 note diminished scale formed from C, provides the tonal basis. The rhythmic organizational structure was initially determined by a technique Joseph Schillinger called fractioning. As the composition grew from this, certain aesthetic considerations were imposed to create some regularity and simplicity of overall form from the irregularity and complexity generated by the fractioning technique.

The Rhythmic Sketch

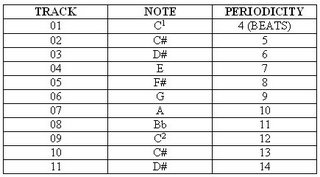

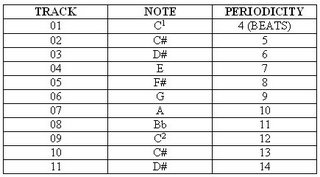

Eleven MIDI sequencer tracks were each assigned a single note from the scale source to play one quarter-note duration on beat 1. Each of these tracks was then set to loop periodically according to the following table:

These loops were then rendered by multiplying each periodicity by a factor of 150, thus creating 11 tracks of varying lengths. Track 1, for example, became 600 beats long (150 bars of 4/4 time) while Track 11 rendered to 2100 beats (14 x 150) or 525 bars of 4/4 time. In order to keep the whole piece within the specified time limit, it was decided at this stage to “double time” all the tracks – a process that halved the durations of notes and the total number of bars.

Concept Draft

Once the sketch had been created, the tracks were mixed down into one so that the rhythmic regularities and irregularities, such as accents caused by the incidence of chord clusters, could more easily be extrapolated. When played back on a piano, the piece at this stage sounded rhythmically interesting. The algorithmic nature of its creation yielded significant amounts of syncopation and rhythmic complexity within the 4/4 metric framework. This, when combined with the ambiguous tonalities of the four diminished seventh chords inherent in the scale source, proved to be aesthetically pleasing, albeit in a sterile and inorganic way. The aim from this point on was to rearrange and orchestrate the draft to make it sound more rhythmically organic.

Ironically, this was achieved by refining seemingly irrational asymmetrical elements of the draft. An 8 bar section was excerpted from bars 187 to 195 of the concept draft and used to create a bass part cell that would form the basis for the arrangement.

Imposing A Form

The method used to determine the bass line in all sections was simple and arbitrary: use the lowest notes of any section excerpted and, where chords occur, delete all notes above the lowest. Transpose to suit the range of an electric bass guitar. The bass figure mentioned above was created this way and used to form an introduction. This 8 bar cell is then repeated four times to create an “A” section. The piano part, when it enters, simply doubles the bass. The opening 16 bars lead the listener to believe there isn’t any regular pulse to the piece. The drums enter to establish the underlying pulse and even a 4/4 beat, though only briefly. This is discussed separately below.

The “B” section (beginning at bar 33) is essentially the bass part created from the beginning (bar 1) of the concept draft score. The zither and zampona parts are the same as the bass line transposed up (an octave and an octave + minor third respectively) however; their entrances have been delayed to create stratified sections like a musical round. These two parts have also been processed with an FX device that causes the zither and zampona notes to echo an 8th note delay an octave below and above respectively.

The piano part that enters at bar 33 is actually the part created for the concept draft reversed and rhythmically displaced so that it begins on the downbeat of bar 33. Specifics of this serendipitous melody will be addressed below.

The Lead Voice that enters at bar 39 was recorded live and in time with the underlying 4/4 metric structure. The durations are irregular although it is the random oscillations of the sound itself that really give it its organic rhythmic quality.

Section “C” marks a point where the periodicity of Track 1 from the original rhythmic sketch (C1 recurring on beats 1 and 3 every bar) ends. In effect, its end creates a tonal shift up a half step to C# and thus a new rhythmic texture – the fractioning of ten periodicities rather than the original eleven. Considerations of the overall length of the composition forced the abridging of this section though similar rhythmic tonal shifts would have resulted if all of the original periodicities had been allowed to play out their full cycle durations.

Section “D” is a recapitulation of the bass and drums from section “A” but with the piano, zither and zampona parts continuing unchanged from section “C”. Doing this created an overall sense of symmetry to the composition through the use of repetition of the “A” section’s rhythmic theme. All parts have been edited in bar 145 to create a definitive end to the composition.

The Drums

This part was created as a 16 bar cell, introduced at bar 17 and then repeated regularly throughout. The first 8 bars of it follow the bass part’s rhythmic displacements of the beat while the syncopated 8th notes played on the ride cymbal bell (bars 7 and 8 of the cell) create a transition to resolve the rhythmic dissonance at the beginning of bar 9 of the cell. The remainder of the drum cell is a (relatively) simple and definite 4/4 funk beat. Like the melodic rhythmic textures, this beat could have been created using fractioning techniques but it was decided to keep it simple so that an underlying sense of recurring rhythmic symmetry could be established and maintained throughout the composition.

Serendipity

The idea to add the reverse piano part came late in the composition process. It wasn’t anticipated that it might sound quite as developed as it does. It begins with a very sparse rhythmic texture in much the same way as an improvised piano solo by Thelonious Monk might sound. As it becomes denser, both rhythmically and harmonically, it develops into a type of rhythmic call-response dialog with the bass and drums that is at its most recognizable and musical in the brief exchange that occurs between bars 113 and 119 in the finished score. Happenstance - Piano Trio Mix.mp3 is the arrangement played by just the piano, bass and drums and has been included so this effect can more easily be heard.

Conclusion

The processes used to organize rhythmic texture and timbres in this composition are, in my opinion, a lot like ink blocks are for a painter. They enable a composer to very quickly generate ideas and a framework in which to work with those ideas. More than this, they are processes that can expand the rhythmic vocabulary of composer and improvising performer alike, not just for ensemble or comping rhythms, but for phrasing of bass, melody and other solo instrument lines.

DOWNLOADS:

Happenstance - Full Mix.mp3

Happenstance - Piano Trio Mix.mp3

Happenstance - Score.pdf

The Concept

Happenstance, as the title suggests, was composed from a few simple musical ingredients to yield a rhythmically complex and surprising score. A single scale source, namely an 8 note diminished scale formed from C, provides the tonal basis. The rhythmic organizational structure was initially determined by a technique Joseph Schillinger called fractioning. As the composition grew from this, certain aesthetic considerations were imposed to create some regularity and simplicity of overall form from the irregularity and complexity generated by the fractioning technique.

The Rhythmic Sketch

Eleven MIDI sequencer tracks were each assigned a single note from the scale source to play one quarter-note duration on beat 1. Each of these tracks was then set to loop periodically according to the following table:

These loops were then rendered by multiplying each periodicity by a factor of 150, thus creating 11 tracks of varying lengths. Track 1, for example, became 600 beats long (150 bars of 4/4 time) while Track 11 rendered to 2100 beats (14 x 150) or 525 bars of 4/4 time. In order to keep the whole piece within the specified time limit, it was decided at this stage to “double time” all the tracks – a process that halved the durations of notes and the total number of bars.

Concept Draft

Once the sketch had been created, the tracks were mixed down into one so that the rhythmic regularities and irregularities, such as accents caused by the incidence of chord clusters, could more easily be extrapolated. When played back on a piano, the piece at this stage sounded rhythmically interesting. The algorithmic nature of its creation yielded significant amounts of syncopation and rhythmic complexity within the 4/4 metric framework. This, when combined with the ambiguous tonalities of the four diminished seventh chords inherent in the scale source, proved to be aesthetically pleasing, albeit in a sterile and inorganic way. The aim from this point on was to rearrange and orchestrate the draft to make it sound more rhythmically organic.

Ironically, this was achieved by refining seemingly irrational asymmetrical elements of the draft. An 8 bar section was excerpted from bars 187 to 195 of the concept draft and used to create a bass part cell that would form the basis for the arrangement.

Imposing A Form

The method used to determine the bass line in all sections was simple and arbitrary: use the lowest notes of any section excerpted and, where chords occur, delete all notes above the lowest. Transpose to suit the range of an electric bass guitar. The bass figure mentioned above was created this way and used to form an introduction. This 8 bar cell is then repeated four times to create an “A” section. The piano part, when it enters, simply doubles the bass. The opening 16 bars lead the listener to believe there isn’t any regular pulse to the piece. The drums enter to establish the underlying pulse and even a 4/4 beat, though only briefly. This is discussed separately below.

The “B” section (beginning at bar 33) is essentially the bass part created from the beginning (bar 1) of the concept draft score. The zither and zampona parts are the same as the bass line transposed up (an octave and an octave + minor third respectively) however; their entrances have been delayed to create stratified sections like a musical round. These two parts have also been processed with an FX device that causes the zither and zampona notes to echo an 8th note delay an octave below and above respectively.

The piano part that enters at bar 33 is actually the part created for the concept draft reversed and rhythmically displaced so that it begins on the downbeat of bar 33. Specifics of this serendipitous melody will be addressed below.

The Lead Voice that enters at bar 39 was recorded live and in time with the underlying 4/4 metric structure. The durations are irregular although it is the random oscillations of the sound itself that really give it its organic rhythmic quality.

Section “C” marks a point where the periodicity of Track 1 from the original rhythmic sketch (C1 recurring on beats 1 and 3 every bar) ends. In effect, its end creates a tonal shift up a half step to C# and thus a new rhythmic texture – the fractioning of ten periodicities rather than the original eleven. Considerations of the overall length of the composition forced the abridging of this section though similar rhythmic tonal shifts would have resulted if all of the original periodicities had been allowed to play out their full cycle durations.

Section “D” is a recapitulation of the bass and drums from section “A” but with the piano, zither and zampona parts continuing unchanged from section “C”. Doing this created an overall sense of symmetry to the composition through the use of repetition of the “A” section’s rhythmic theme. All parts have been edited in bar 145 to create a definitive end to the composition.

The Drums

This part was created as a 16 bar cell, introduced at bar 17 and then repeated regularly throughout. The first 8 bars of it follow the bass part’s rhythmic displacements of the beat while the syncopated 8th notes played on the ride cymbal bell (bars 7 and 8 of the cell) create a transition to resolve the rhythmic dissonance at the beginning of bar 9 of the cell. The remainder of the drum cell is a (relatively) simple and definite 4/4 funk beat. Like the melodic rhythmic textures, this beat could have been created using fractioning techniques but it was decided to keep it simple so that an underlying sense of recurring rhythmic symmetry could be established and maintained throughout the composition.

Serendipity

The idea to add the reverse piano part came late in the composition process. It wasn’t anticipated that it might sound quite as developed as it does. It begins with a very sparse rhythmic texture in much the same way as an improvised piano solo by Thelonious Monk might sound. As it becomes denser, both rhythmically and harmonically, it develops into a type of rhythmic call-response dialog with the bass and drums that is at its most recognizable and musical in the brief exchange that occurs between bars 113 and 119 in the finished score. Happenstance - Piano Trio Mix.mp3 is the arrangement played by just the piano, bass and drums and has been included so this effect can more easily be heard.

Conclusion

The processes used to organize rhythmic texture and timbres in this composition are, in my opinion, a lot like ink blocks are for a painter. They enable a composer to very quickly generate ideas and a framework in which to work with those ideas. More than this, they are processes that can expand the rhythmic vocabulary of composer and improvising performer alike, not just for ensemble or comping rhythms, but for phrasing of bass, melody and other solo instrument lines.

Friday, November 04, 2005

Sagittarian Composers & Performers

This list grew out of the fact that Beethoven and me share the same birthdate. It turns out that quite a few of my favorite composers and performers are also Saggitarians. Make of that whatever you like...

Beethoven, Ludwig van (December 16, 1770 - March 26, 1827)

Berlioz, Hector (December 11, 1803–March 8, 1869)

Britten, Benjamin (November 22, 1913 – December 4, 1976)

Brubeck, Dave (December 6, 1920 - )

Carmichael, Hoagy (November 22, 1899–December 27, 1981)

Hendrix, Jimmy (November 27, 1942 - 18 September, 1970)

Jones, Spike (December 14, 1911 - May 1, 1965)

Kenton, Stan (December 15, 1911 - August 25, 1979)

Kodály, Zoltán (December 16, 1882 – March 6, 1967)

Messiaen, Olivier (December 10, 1908 – April 27, 1992)

Morrison, Jim (December 8, 1943 – July 3, 1971)

O'list, David (December 13, 1948 - )

Osbourne, Ozzy (December 3, 1948 - )

Pastorius, Jaco (December 1, 1951 – September 21, 1987)

Rodrigo, Joaquín (22 November 1901 – 6 July 1999)

Rubinstein, Anton (November 28, 1829 – November 20, 1894)

Schuller, Gunter (November 22, 1925 - )

Shaffer, Paul (November 28, 1949 - )

Sibelius, Jean (December 8, 1865 – September 20, 1957)

Sinatra, Frank (December 12, 1915 - May 14, 1998)

Smith, Jimmy (December 8, 1925 - February 8, 2005)

Strayhorn, Billy (November 29, 1915 - May 31, 1967)

Tureck, Rosalyn (December 14, 1914 - July 17, 2003)

Waits, Tom (December 7, 1949 - )

Zappa, Frank (December 21, 1940 - December 4, 1993)

Other Interesting Sagittarians

Blake, William (November 28, 1757 – August 21, 1827)

Bundy, Theodore Robert "Ted" (November 24, 1946 – January 24, 1989)

Clarke, Arthur C (December 19, 1917 - )

Dick, Philip K. (December 16, 1928)

Disney, Walt (December 5, 1901 – December 15, 1966)

Gilliam, Terry (November 22, 1940 - )

Marx, Harpo (November 23, 1888 – September 28, 1964)

Nero (December 15, 37AD – June 9, 68AD),

Nostradamus (December 14, 1503 – July 1, 1566)

Scott, Ridley (November 30, 1937 - )

Twain, Mark (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910)

Vampira (Actress Maila Nurmi, December 21, 1921 - )

Interesting Events - December 16

1773 - The Boston Tea Party

1893 - World premiere of Antonin Dvorak's "New World Symphony"

Beethoven, Ludwig van (December 16, 1770 - March 26, 1827)

Berlioz, Hector (December 11, 1803–March 8, 1869)

Britten, Benjamin (November 22, 1913 – December 4, 1976)

Brubeck, Dave (December 6, 1920 - )

Carmichael, Hoagy (November 22, 1899–December 27, 1981)

Hendrix, Jimmy (November 27, 1942 - 18 September, 1970)

Jones, Spike (December 14, 1911 - May 1, 1965)

Kenton, Stan (December 15, 1911 - August 25, 1979)

Kodály, Zoltán (December 16, 1882 – March 6, 1967)

Messiaen, Olivier (December 10, 1908 – April 27, 1992)

Morrison, Jim (December 8, 1943 – July 3, 1971)

O'list, David (December 13, 1948 - )

Osbourne, Ozzy (December 3, 1948 - )

Pastorius, Jaco (December 1, 1951 – September 21, 1987)

Rodrigo, Joaquín (22 November 1901 – 6 July 1999)

Rubinstein, Anton (November 28, 1829 – November 20, 1894)

Schuller, Gunter (November 22, 1925 - )

Shaffer, Paul (November 28, 1949 - )

Sibelius, Jean (December 8, 1865 – September 20, 1957)

Sinatra, Frank (December 12, 1915 - May 14, 1998)

Smith, Jimmy (December 8, 1925 - February 8, 2005)

Strayhorn, Billy (November 29, 1915 - May 31, 1967)

Tureck, Rosalyn (December 14, 1914 - July 17, 2003)

Waits, Tom (December 7, 1949 - )

Zappa, Frank (December 21, 1940 - December 4, 1993)

Other Interesting Sagittarians

Blake, William (November 28, 1757 – August 21, 1827)

Bundy, Theodore Robert "Ted" (November 24, 1946 – January 24, 1989)

Clarke, Arthur C (December 19, 1917 - )

Dick, Philip K. (December 16, 1928)

Disney, Walt (December 5, 1901 – December 15, 1966)

Gilliam, Terry (November 22, 1940 - )

Marx, Harpo (November 23, 1888 – September 28, 1964)

Nero (December 15, 37AD – June 9, 68AD),

Nostradamus (December 14, 1503 – July 1, 1566)

Scott, Ridley (November 30, 1937 - )

Twain, Mark (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910)

Vampira (Actress Maila Nurmi, December 21, 1921 - )

Interesting Events - December 16

1773 - The Boston Tea Party

1893 - World premiere of Antonin Dvorak's "New World Symphony"